System Architecture

The Impetus

SODA 2.0 came out of our interest at Socrata to create a simple API that could be used across any open data service. The purpose is to allow applications and third parties to only need to become familiar with a single API. We wanted to balance between an API that was rich enough to be useful for anything from mobile applications to R analysis tools, while being able to protect our internal services from getting “melted” by queries that ran in O(n^2) time.

What we came up with was SODA 2.0. This product provides a clean interface to update data, as well as a clean SODA Query Language (SoQL) for querying data as well. You can learn more about these protocols on Socrata’s dev site (http://dev.socrata.com/).

That said, SODA 2.0 and SoQL only solved part of the problem. The larger technical challenges were around building a backend that can actually service these requests. When we looked into solving these challenges, we noticed a few things:

- Different data sets often need different storage and performance tradeoffs to operate how we want them to. These tradeoffs are often based on the size of the data set, as well as how often it’s updated.

- Different data sets often require different updating semantics. What this means is that if a customer is updating their crime data set every hour, then they want to have either all the crimes get added, or none of the crimes get added. This way, it is clear how to deal with errors. For example, if an organization is updating the locations of busses every 30 seconds, often it is better to write what you can and fail some of them. This is because failures will be rare and new data will be coming in 30 seconds anyways.

- There are many operations outside SODA 2.0 that an open data infrastructure should provide. These are more tied to services around syncing data or alerts. This is all tied into a desire to create an “open data substrate” that will make it easy for data published as open data to be used, consumed, and found in as many ways as possible.

The Architecture

We addressed these issues by creating an architecture that does a couple of important things:

- We focused on creating a layer that could sit above many types of data stores, so we could standardize on using APIs like SODA, but not tie ourselves to any one implementation for queries or updates.

- We built out the concept of a “truth” store that is updated by users, as well as more performance “secondary” stores that may be a little out of date, but can be deeply optimized to faster queries and lookup operations.

- We split out the read & write paths, so we could give transactional semantics to writers, but provide faster, lock-free reads for anyone using the data.

- We focused on the mechanisms needed to provide bullet-proof synchronization between the transactional “truth” and the other stores we use.

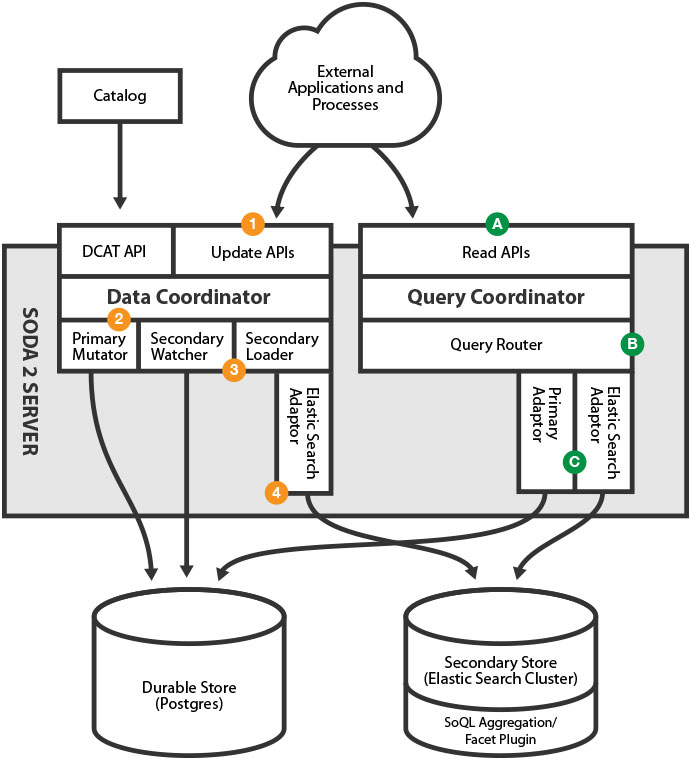

The Write Path

- An application or process starts off the whole thing by sending an insert, upsert, or delete operation to the SODA Server. This will be exactly the same in format and semantics as what is covered in the Socrata SODA API documentation on http://dev.socrata.com/.

- The request will be turned into a series of more granular operations called “mutations” and passed into the Data Coordinator which will then run those mutations over the truth store (in this case Postgres) in a transactional way.

- After the Data Coordinator is finished, the Secondary Watcher will wake-up and look to see if there are any changes in the truth store that have not been synced lately. This may often be called right after the truth is updated, but in order to be resilient to crashes and other failures, the design does not require this.

- The adaptor for the secondary store, in this case Elastic Search, then imports the data from the primary. The mechanism is built so that it will only get notifications for the records that have changed, however, in the case of dramatic failures or having to rebuild, can also do a full re-sync from scratch.

The main components that implement the write stages are in the data-coordinator repository (https://github.com/socrata/data-coordinator) for steps #2 & #3. Then the soql-es-adaptor repository for step #4 (https://github.com/socrata/soql-es-adapter), in particular the store-es project in it.

The Read Path

- An application sends a SoQL request to the server. This will be parsed with the parser in soql-reference, and will be exactly the same in format and semantics as what is covered in the Socrata SODA API documentation on http://dev.socrata.com/.

- The Query Coordinator will make a determination about which store the request should go to. In the future, there may be many different secondary stores and more sophisticated ways to route requests, however, for this version there will only be routing for “truth” and everything else.

- The Query Coordinator will then hand off the query to the appropriate adaptor, which will execute the query against the correct store and return the appropriate C-JSON payload.

In this flow, step A uses the soql-reference project (https://github.com/socrata/soql-reference) for lexing, parsing, and analyzing the SoQL that is passed in. You can also look in that repository for a file describing a more precise language definition of SoQL. Step C is then mainly implemented in the adaptors. The most interesting of these right now is the Elastic Search adaptor in https://github.com/socrata/soql-es-adapter.

Connecting the Dots

For the last part of this architecture discussion, I wanted to take a little section to show a few examples of where we are looking to take this architecture.

Extending the SODA Server

One of the primary goals of the SODA Server is to easily be extensible for other secondary or truth stores that people want to add. For example, large datasets may want to live on a Hadoop or HBASE cluster. Real-time data may want to have a Cassandra truth store and relax the transactional guarantees (but keep the same APIs). Frequently accessed datasets may want to live on a secondary store with all SSD storage. Less frequently accessed datasets may want to live on a secondary with big, cheap disks. Building out the appropriate architecture will allow the SODA Server to handle these many cases in consistent ways.

In addition, though, there is a more interesting approach we’ve talked about where we can add functionality as additional secondary stores. For example, one interesting operation we would like to see as part of an open data substrate is the ability to keep datasets synchronized across different stores. Whatever protocol we decide on for this synchronization could be implemented by a secondary store that can be reliably notified of changes and then create a purpose-built data structures to be able to provide the synchronization APIs.

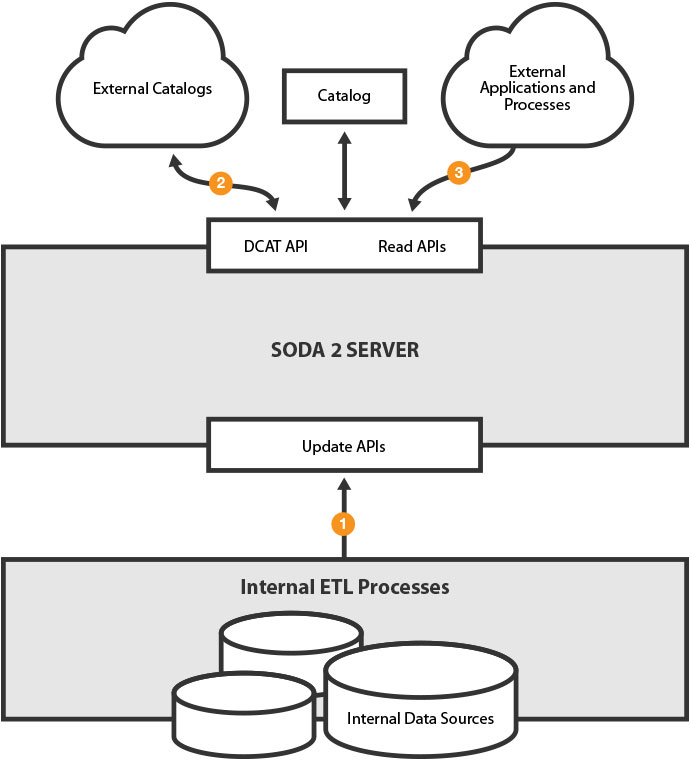

SODA Server in the Open Data Ecosystem

In the Open Data Substrate, there are two main types of systems: Catalogs and Data Stores. The SODA Server is a Data Store. Its purpose is to make open data more useful than simply a downloadable CSV, while providing standard APIs to allow other processes to access it.

- Internal ETL processes can publish data from internal systems. Most commonly, these are systems like the 311 and 911 systems. However, they can use any tools that use SODA.

- External catalogs can point to the SODA 2.0 server and use the DCAT API to retrieve the list of datasets and their metadata to import.

- Applications, visualizations and analytic tools can use the SODA API to access the data.